From Sounds to Script: How Montessori Children Learn to Write

In Montessori classrooms, the process of writing begins long before children begin to hold a pencil. We start with rich oral language experiences, exploration of sounds, joyful movement, and a growing awareness that the symbols of written language carry meaning.

By the time children begin the recording process, that is, writing words on a surface, they have already done enormous preparation. They know the sandpaper letters so well that they can trace them blindfolded or “write” them in the air. They have composed countless words using the Moveable Alphabet, experimenting with sounds and meaning long before their hands are ready for conventional writing.

And then… one day… they are ready to put chalk to board.

This is the beginning of a beautiful and empowering journey.

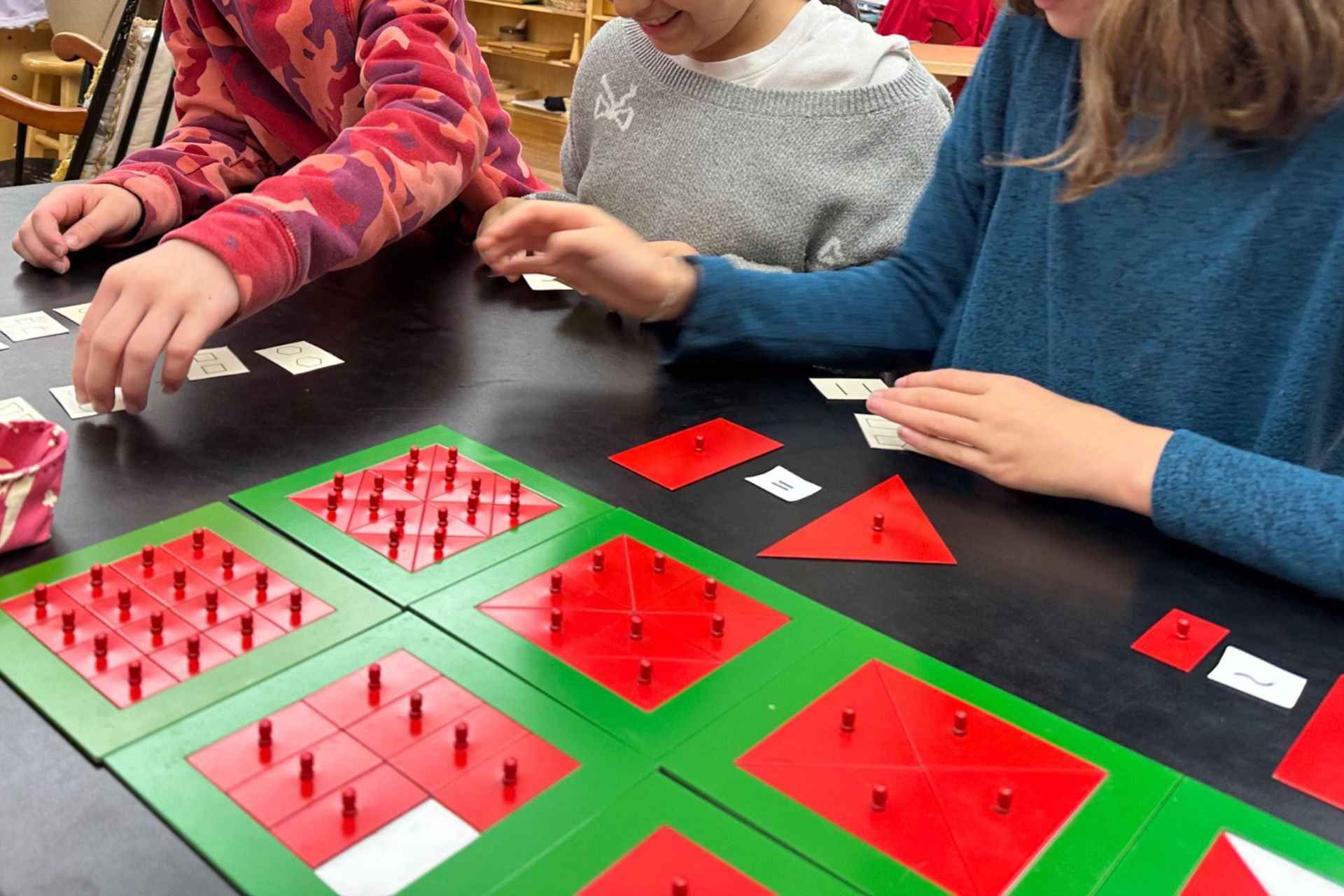

The Materials That Support the Journey

To help children make the transition from forming words with the movable alphabet letters to recording them on a surface, we offer a thoughtfully prepared environment that can include:

- Small chalkboards (blank, lined, or squared)

- Large wall-mounted chalkboards

- Containers of sharpened chalk and half-erasers

- A writing supply station with paper in various narrow sizes

- Pencils and underlays as needed

- Accessible writing surfaces around the room

These materials invite practice without pressure, exploration without permanence, and repetition without fatigue, all of which are essential at this stage of development.

Step One: Writing Words with Chalk

When a child has composed a list of words with the Moveable Alphabet, the guide gently introduces the chalkboard: “Let me show you something you can do with the words on your rug.”

The child brings one word to the table, and the guide may make a point to notice how the letters connect and flow. With a piece of chalk in hand, the child can attempt to write the word on the chalkboard. For many children, this moment is astonishing, as they suddenly realize, “I can write!”

Over the next several days, the child chooses words, writes them, erases them, and writes again. During this time, the child naturally refines:

- the direction of writing,

- the connection between letters, and

- the placement of letters along an invisible horizontal line.

This is joyful, purposeful work. And the chalkboard provides endless opportunities for clean slates!

Step Two: Introducing the Baseline

Once the child is comfortably writing words, we introduce the idea of a baseline, which is the line on which most letters sit.

We use a simple ruler to draw a single line across the chalkboard and explain: “I’m using this line to show where the letters sit.”

The child thus begins to understand that writing follows a structure, including the realization that letters aren’t merely floating symbols but exist in space in predictable ways.

Step Three: Baseline and Waistline

As the child’s control increases, we add a second line: the waistline. This is the space where most lowercase letters rise up to, and introducing it helps children refine the size and placement of their script.

Using pastel chalk, we shade the space between the baseline and waistline, giving a soft visual guide. Over the next several days, the space becomes a little narrower. And then narrower still.

Eventually, the child works confidently on a nine-lined chalkboard, and from there, we transition to paper. Many children around five-and-a-half naturally begin to prefer writing directly on paper rather than returning to the Moveable Alphabet. They have internalized the shapes of letters, the structure of words, and the flow of writing.

It is important to remember: the natural size of children’s script varies. Some begin writing very small, others larger. We follow the child rather than a rigid sequence.

The ultimate goal is simple and elegant: to write confidently on a single line.

What This Work Supports

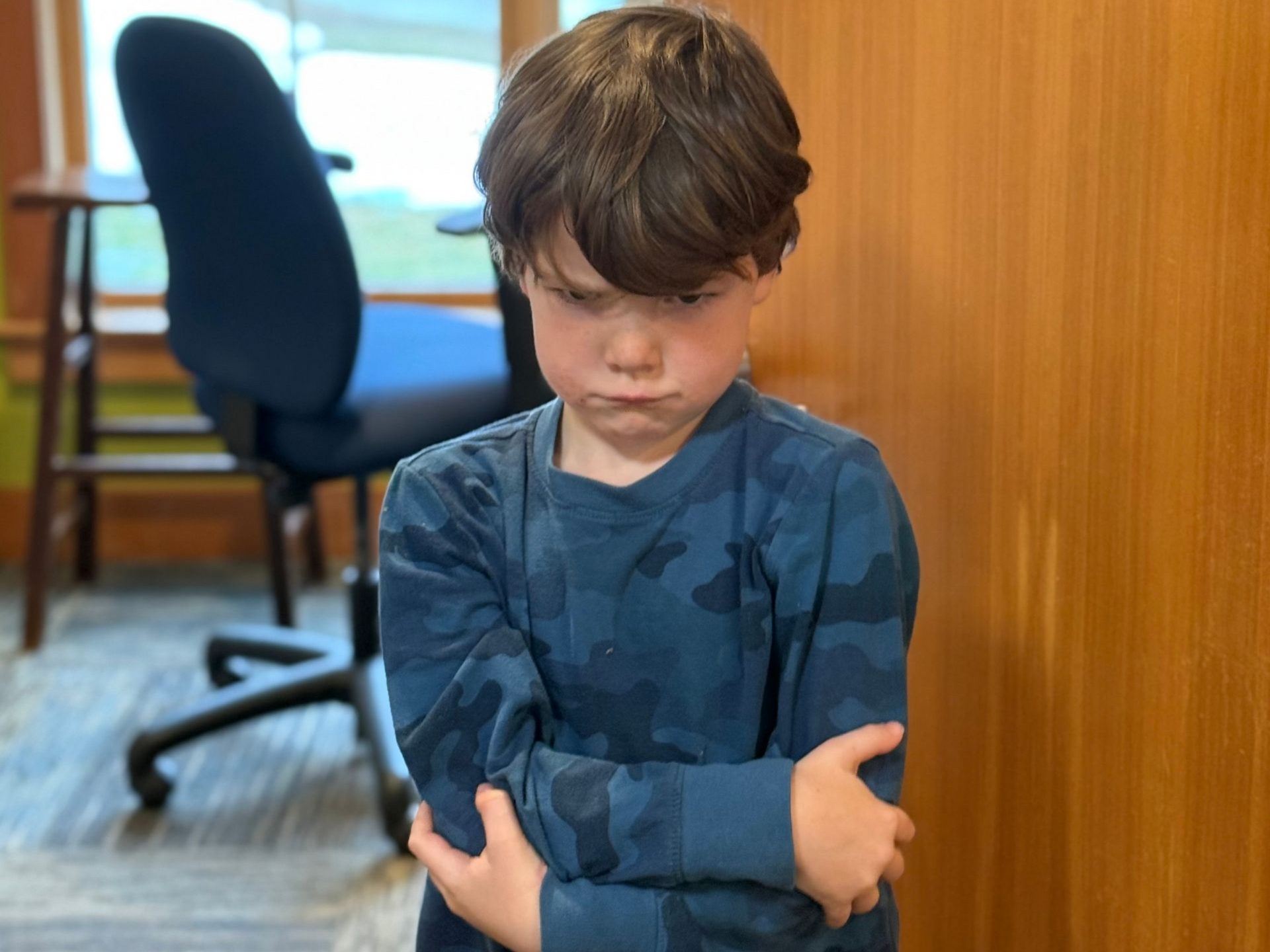

A child who moves through this sequence with joy and readiness:

- develops beautiful, legible handwriting,

- gains confidence in written expression, and

- understands that writing is a tool for communication.

This is monumental work for a young child. It marks the moment when their mind and hand unite to express their own thoughts. Most importantly, writing unfolds naturally when the groundwork has been laid with care.

Schedule a tour of our school in Lenox, MA

to see how we honor this journey with care and intention.